1.

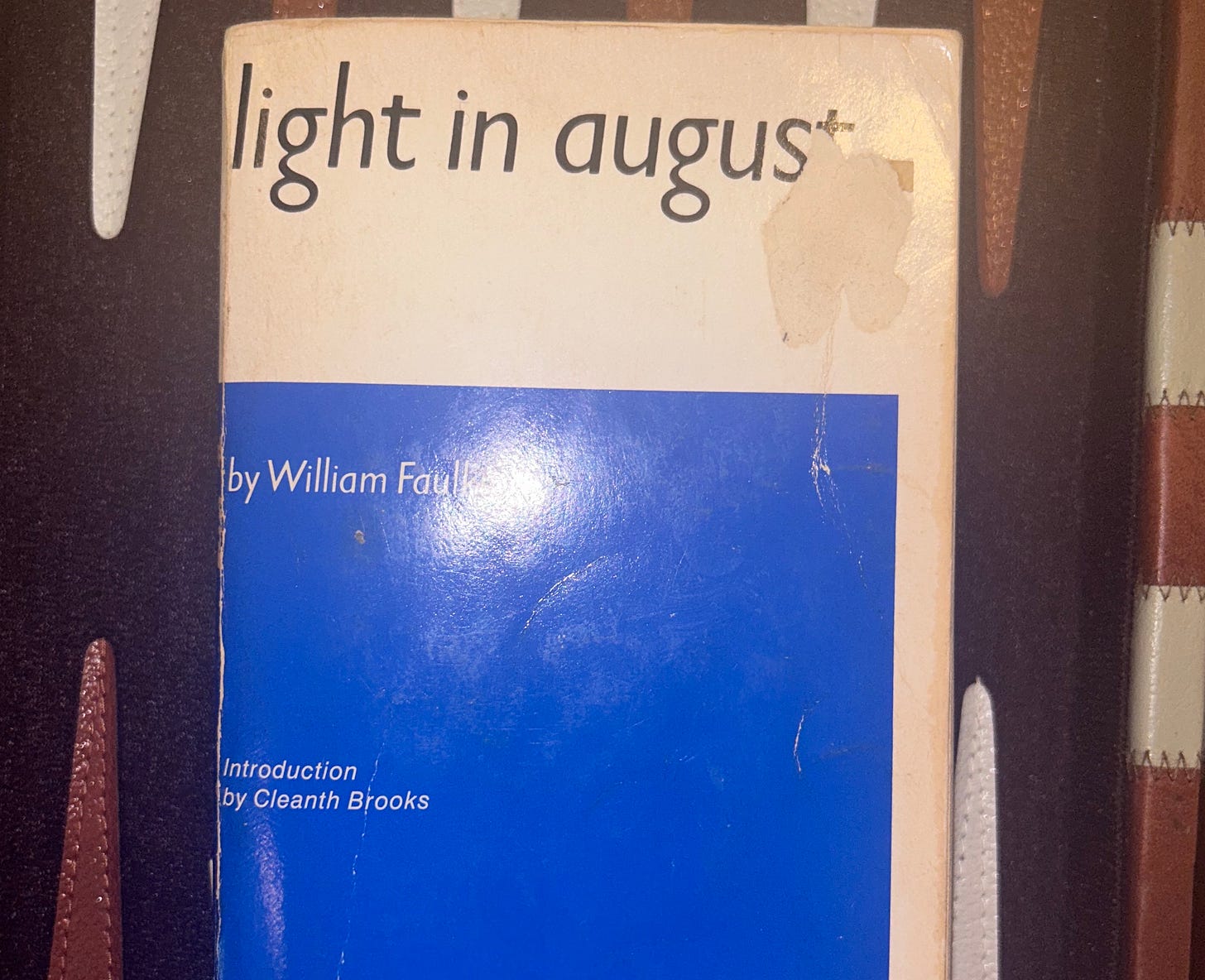

I showed you my mother’s high school copy of Light in August, a blue rectangle on the cover.

She marked up the front when she was seventeen—“1932, After Tender,” penciled in her sloping legible print, exactly as it is now. I found my father on the fifty-sixth page in blue—all-caps, almost screaming he penned “CRUCIFIED.”

I asked you to make sense of it, brought to you my questions. You leafed through and I was suddenly embarrassed; as if in giving you my parent’s writings I revealed my mind gray and hellish. “He underlined everything I would have,” I said.

“You’re part of something bigger. An unseen system, that’s all,” you said, looking down at the spine crack, pulling at a hair sticking up in the adhesive. “Did you have pets?”

I took the book and examined the sliver, blonde and stiff. “Binding splinter,” I said, thinking about my mother gray and fuzzy in those pages and Faulkner’s “it was blue, dark blue” and my father’s hand above, also blue: “DEATH.”

Imagine my mother on green carpet propped up on a floral pillow listening to Outlandos D’Amour by The Police on a cheap record player. Her brother is home from college but out. Her father is not yet dead and her mother is busy collecting.

Imagine she returns year after year to find the same green carpet, every chip bag washed and pressed into little origami strips and stored in a banker’s box in the attic. Imagine thousands of unread newspapers stacked neatly to chin-height, also in the attic, molded brown and reeking—their life accumulated and dying at the hand of these objects. Everything must be sold, even the house, but she keeps the Hermès scarf and glass animals you can fit in your palm.

Imagine my father greasy and sweat-bloomed on a forklift, the third child of six in a single-story house south of Chicago. His father is sunning somewhere in Phoenix and his mother is working. Neither of them dead yet, but soon. Imagine he never returns to the single-story, instead, gets a comp-sci degree and moves north for a job in the city. He prays he won’t father a son and God gifts him me. Imagine I’m on a chair mat beneath his desk, lifting the edge. A few years later he shepherds me into a train car, eyes decorated in the city.

My mother handed over Faulkner to him as I hand it to you now, past and future folded and stabbed like a letter, twin holes gaping. The book transcribes the end but Los Angeles embodies it, the end itself.

2.

They say a hurricane is coming so everyone is staying home. The people from Texas are stocking up on canned goods and toilet paper but I don’t think the winds will manage the mountains.

Before the hurricane I walked past a crime scene on Sunset. Someone prone and dead, a flash of brown trousers through an open corner of the police tent. When they cleared the tarp, three stones and a few flowers from Trader Joe’s lay in an arc on the astroturf where it happened.

A week later the flowers were gone replaced by several Lime scooters. I wondered if the green plastic tufts still had remnants of the body, little particles of dead or brown threads from the pants? If the people who parked the Limes knew just seven days prior there was crime scene tape.

3.

My friend texted me about the 5.1 earthquake. “What next? Locusts?” she wrote. I thought earthquakes would be like car crashes, harsh and metallic. But the ground feels supple, released from gravity for a few trembling seconds. Turbulent and floating as an airplane in descent.

It was the fourth time I felt the earth move and the third in California. The first was in college when I awoke thinking my roommate was having raucous sex or something because I had never heard of earthquakes in Oklahoma. Famously tornados were a problem.

Days when the sky emerged green like a bruise vomiting wind and the stadium whined an alarm, we waited for the all-clear from the city. There was time to kill so we drank through the afternoon in homes with no basement shelter and watched the signs: trees collapsing, torrential downpour, telephone lines snapping and the sky, seemingly cloudless but we knew better—we were inside the clouds. Green inhaling everything and bolting it down.

There were windless moments too, everything silent except for that high alarm, holding.

4.

Rain is falling again. It doesn’t rain often here but when it does you remember it. Wetness sticks—on sun-lapped spots on your windshield, pinpricks of smog edged in sidewalk cracks beneath an awning or balled up on shedding trees.

The rain doesn’t fully disappear until an exceptionally hot day when the river empties into the sky with the trash essence. LA rain doesn’t clear things away, not like Texas where storms carry cars condoms oil slick sign postage bodies downstream, away away. Texas disappears things but LA is an echo. We are left with it all, all again, re-filled like a dog tonguing at his own sick.

5.

“Killers are very human. Maybe the most human of us. An excess of feeling I guess,” you said to me on Vermont. People were stopping by, saying hello, talking about Domenico Starnone and proposals and translation.

The sky darkened and I looked up. Silvery and weak, edged in black. Shining. Greyscale like television.

6.

It’s sunny today and they are taking out the trash. The air is alive with filth, oxygen filmy with smog and city scent. I feel it enter and exit my lungs, imagine the new-not-new air permeate the Edgecliff jacarandas, touching us and morphed into carbon. We become the air (a card trick of sorts). Does this make the air alive too? No. Yes. Can air die?

The permanence of a plastic cup for instance is baffling considering its single-use functionality for holding liquid to drink then dispose of twice. It passes first through us and then tunneled back into water treatment facilities or the ocean, spiraled away away. Liquid cycles but cups don’t transform don’t disintegrate, only shatter, pile up. Does immortality preclude aliveness? Things are piling up. Piling somewhere someplace.

7.

Imagine the moment of contact hand to body of a hit. For a moment imagine you hit me. My skin ripples over bone and ligament and blood, you in the dent, covering. In this merging you are in me for the rest of my life and beyond probably. The maggots eat my skin and yours. When the incinerator puffs putrid me-smoke, you exist there too—our particles dispersed between (perhaps inside) the air and rained down with the wet. Again and again we exist together, strangely alive and married in our deadness.

Can you imagine all this, the breathtaking scale in even the smallest unit of violence? Do you understand how the world could be over and still turn?

8.

Mid-summer I found a cat beneath the hard shadow of a construction truck, its little eyes staring open and relaxed with the preternaturally still look of gone things.

Movement can be a sign of aliveness—if a patio chair flies in a storm could we mistake it for alive if we did not already think of it as an object without a brain? Or an animatronic snake writhing toward a screaming kid, Frankenstein-ed from a remote control into the appearance/aesthetic of aliveness. In this case the remote serves as a kind of brain.

We think of a plant as alive but not the pot that holds it though both are made of substance that is real. But the pot is not in flux and therefore not “living,” separate from minute changes of a being as it flirts with deadness. But an explosion, the splitting of an atom and its chain reaction of light feels alive enough. Or the way my car feels animalistic under me on the freeway, another object in flux. I once wrote that driving when done correctly can “make the inanimate breathe.”

9.

Mountains here cut the sky, I thought, turning onto PCH. I saw them putting up rows of flags for the holiday, cars stacking up and fuming the beach. In California nothing beautiful can be let alone—it must be always be sold, presented to the world and the world to it with smacking unstoppable force like a rushing crowd at a concert.

If we separate nature from itself, diminish it, could we then hold it? We embedded plutonium in the land, paved and refined it, chucked designer sand beside the Riviera, put up white letters on the side of a mountain and erected museums cliff-side. We tried to make the world our own as if our punishments did not cost something (signs/causality/effect/phenomena). We believe it will not retaliate.

10.

You showed me an ant upon your forearm in the bookshop. Smiling. You were pleased. Life came to you, dark hairs freckled skin like a freeway. I wanted to crush it between my index and thumb. Burst tiny drops of blood black just to check its insides.

11.

When I was a child I was sharp and then sharpened, whittled and peaking. My soul (mind if you want) overflowed, swimming in feeling and it gave me the capacity to hurt. Light was extreme, everything a fever. My body flung out cutting and eating and starved, something lurked which could allow me to take, to kill.

Almost without deciding to do so I took the feeling and threw it down, blunted myself. The base of a triangle never again the apex, unblooded. In me now are degrees of ice. If intention is vital when it comes to souls does this make me saved?

12.

“At some point you will have to choose goodness,” I say.

Imagine I am on the bed coated in filmy him-stuff, glittering with it. I am totally unreachable even to myself. My body suffers, he thinks. “I’m skittish I suppose,” I say, framing it in a way he’ll understand—horse-like, still ridable. It changes nothing; we both already think of me as half-animal.

We were talking about the snake and Genesis, how the woman the snake and the tree were one and how corruption only exists in cracked souls. “I am bigger than you,” I say. Imagine I am the snake, supple and undulating in his hands—strangling, pressing upon the world like deep ocean. Imagine I evacuate every feeling and unleash it on the street.

13.

The entanglement of humans non-humans and human-made objects (the final being by far the most permanent) is not difficult for me to conceptualize but to take all of these things, every object in the universe and not place them in orbit around humans is a bit of a mind-fuck to me.

It is through our own actions and capitalist ambitions that we are here, the world doomed but even that implies a futural end. As if it were not already real, already everywhere all around us all of the time. As if we have not already done the closest thing to obsoletion without touching zero a hundred thousand times over.

14.

I am stopped up with thought, gagging on it. Events slide by. I went to dinner on Hillhurst and couldn’t stand to talk. I wanted to go. I wanted to be sick. Sometimes people make me sick and I know with absolute certainty there is something rotten in me tamped but always feeding.

Ideas come to me when pain ceases to feel real only throbs. I can hold it there and let it flow, perfected. Sometimes it is an outpour. Draining like a vacuum I become clean and pure but totally limp.

15.

“New York jostles,” you said again on Vermont. You were talking about friction, millions of bodies clustered and bouncing like a biome. “That’s what’s so inspiring about it. Just constant stimulation.”

“I’m never moving to New York,” I said for the umpteenth time that week then something about the ecology of cities and how language forms for me in silence. In Los Angeles I can ooze and sprawl with civic expanse. Unearth the unuttered, extended and revelatory. In truest black colors appear.

16.

After dark by the LA river (another poisonous thing emptying into the Pacific) I looked to the murky waters, listened to its sludgy bubbling and the mauve silent sky above.

That night I watched a cockroach scuttle encouragingly toward a bar entrance like it was just another lank-haired girl in line. I want you to know it was gorgeous, red-black and brilliant and revolting. I want you to know I thought about taking it home in a jar, this immemorial thing, and feeding it leaves or whatever roaches like, painting it with nail polish and giving it a name. I wanted to ask it questions about Blake and his Nature poetry, sentience and God—antennae twitching yes. No.

17.

Blogs about Los Angeles talk about live shows El Prado Stories dinners downtown weddings and celebrity encounters but never the weather. Occasionally they mention its sameness but there is so much to write about in its minor gradations. Parse sunny from half-sunned, rainy from grayed, separate night-cooled evaporating, tense with mosquitos, from doggish skin-air when the temperature within one’s body is the same as without.

Hell resembles August in Van Nuys but there is heaven also. It usually materializes in June, almost always in the Canyons.