I have to thank Emily, who edited this piece, a million times, in a million ways. For ten years, we’ve exchanged writing, books, movies, and 3-hour rants about pop music. My first and best supporter, my comrade, and one of the smartest people I know. Read her newsletter Emily for President for thoughtful, well-researched (but fun!) writing on the culture at large.

Morning Colors

I.

For a year William Blake followed me. Last summer, I read his poetry collection at Laurel & Hardy Park. He popped up at an antique bookseller in San Francisco and in a Patti Smith song. Four months later, he showed up in a big way at a Spanish-style bungalow in the Pasadena art colony—he was everywhere in that house, down to tiny depictions of Milton’s Paradise Lost on the bathroom tiles. I kept looking for signs (sometimes literally, like when I gasped driving past Blake Avenue in Cypress Park). I wrote him into a screenplay set in San Francisco.

I watched the scrolling headlines and grew desperate for answers about Nobodaddy, politics, and God so I bought Timothy Morton’s new book Hell: In Search of a Christian Ecology. I shouldn’t have been astonished to find William Blake on the first page, the Romantics’ “Daddy” of nature and God, but I was. Morton writes what I’ve thought so often this year: “I have to sound like Blake.”

I was sure there was something more out there, but I had no desire to return to the church and Californian spirituality didn’t do it for me either. Neither did the Hubble pictures or crystals or Buddhism. Blake would have the answers, I thought. Blake by way of Timothy Morton would tell me the truth.

When I was eleven, I was easily awed, totally taken in by a man atop a black stage, illuminated by a projector screen, calling for my apology for being alive. Evangelicals want nothing more than for you to beg: beg for life, forgetfulness, forgiveness, love. For them, unfastened hunger (Simone Weil, Gravity and Grace) is spiritual sustenance. The church wants you to deny the world in favor of the divine.

Blake moves me because he flips Christianity on its head: what if it’s the world that’s divine?

His poetry explains something in me no psychics, gnostics, tarot readers, or pastors ever did: why I feel closest to God on a blisteringly hot day encountering a pile of trash, wet from day-old rain on the sidewalk, or staring out at a city full of fireworks, blubbering about the wishful nature of Los Angeles, every technicolor explosion like a prayer. When I look out the window and fix on a slice of blue sky, I see God as “Infinity in the palm of your hand” (Blake, Auguries of Innocence).

I described reading Morton as one big “download,’ but with every new puzzle piece in the shape of ecology or Gnosticism-is-bullshit, the picture seems both brighter and darker than ever. Gleaming, full of holes. I’d like to turn off my brain and wake up with understanding, but the questions keep me up, agitated and alive like a sodium bicarbonate mixture; shaken up, whirring with it.

Everything feels finely woven like a spider’s web twirled around a twig, sticky and intricate, full of entanglements imperceptible to the human eye. It’s coming in intermittent gasps and I’m struggling to hold onto most of it, so bear with me. None of this is finished.

II.

In 2022, young activists threw a can of Heinz tomato soup at a Van Gogh in the name of Just Stop Oil. The world was outraged—isn’t there something better, more useful these kids could be doing with their time, like buying Carbon Credits?! The people annoyed at the stunt don’t get that “the point of environmentalism is not to shout at the TV. The point of environmentalism is to be on the TV” (Timothy Morton, Hell). But okay. Phoebe and Anna gave climate change a “bad name” by defacing a painting that ended up being fine anyway. “Congratulations on the infinite regress.”

Policy pushes back so art pushes forward. Or is it the other way around? Replace “environmentalism” with any “ism” (good or bad) and you get my idea. Art should be purposeful. Blake’s work isn’t just beautiful, it’s persuasive. Art for the sake of itself (without motivation, drive, or ideology) is just a picture on the wall. Van Gogh’s sunflowers are just sunflowers.

In my case, I write about women, but I do not write about what they are like. I couldn’t if I tried; I don’t know what women are like. People are different from one another and no glittering, pink homogeny (no matter how joyful or well-meaning) can capture such a wide, varied spectrum. It feels a little bit imaginary to talk about what it is to be a woman in the world beyond oppression.

I’m sorry, this is bleak. It’s probably not a good idea to wholly distance ourselves from gender at a moment when the war for bodily autonomy (gender-affirming health care and abortion rights) is explicitly gendered. Those affected are in no way necessarily women, but all live in the nebulous “other” checkbox, literally defined by what they are not: cis, male, straight. Yes, there’s hope and community and protest to the glitter, but I find myself wincing at terms like “female gaze” and “female rage.” What can those terms mean except as a response and/or counteraction to oppression? Isn’t there something bigger out there?

In cinema, “female rage” doesn’t mean moving images of a person losing their shit who just happens to be a woman. What defines it is our reaction or lack thereof to the images: we are not frightened. Her outburst is framed as justified, righteous, and above all cathartic. Imagine the same scene but gender-swapped. We might instinctively pull back; a man’s anger is dangerous, but when the heroine snaps, we roar with approval. It’s sympathetic comeuppance. Revenge.

A recent exception to the “female rage” problem is Julia Ducournau’s Titane, whose female protagonist commits violence not borne of catharsis, but desire. She fucks a car and then, without bloodlust or justification, murders someone. There’s a simplicity and genderlessness to the act that runs through the rest of the film. In the wake of the murder, she goes on the run as a boy, posing as the missing son of hyper-masculine, roided-out fireman Vincent, and a tenuous bond forms between the two. Titane does not depict reality, but a kind of utopia.

In Ducournau’s world, gender and gender presentation are unstable, inconsequential phenomena in the face of metal; the visceral materiality of the machine. Motor oil (like genitalia) is animalistic and erotic, but not gendered. Titane swims in questions of presentation and transness but deliberately evades clarity on the subjects. The protagonist becomes the machine, unearthing something transmutable, something of the soul. A 21st-century Orlando for metal-fucking.

Granted, my personal feelings regarding gender are comparatively limited and very privileged (I was born, present, and identify as a woman), so it makes sense that my knee-jerk response to art and online discourse about womanhood is either impatience or frustration. But the gender essentialism-tinged arguments we have with one another (take the “bear versus man” debate) feel crushingly restrictive. Nobody wants to have their identity reduced to defensive reactions. Again: people are different from one another.

That being said, aesthetics linked to women and queer folk, historically objects of ridicule in white Western culture, have had a pop-culture renaissance in the past few years, and I’ve enjoyed every fucking minute of it. Those who dismiss aesthetics as frivolous or unimportant don’t understand how symbols (good and bad) are real, powerful forces in our world. Think of the Eucharist (bread=body, wine=blood) or a Blue Lives Matter bumper sticker. It’s a transference. One thing becomes another, distilled into a bigger, more universal picture.

The fascists have it down—just look at any alt-right meme page, and you’ll get the sense of just how efficiently modern symbols can transform an idea into salient, frightening action. Generally, the left doesn’t believe in symbols in the same way because to them, “propaganda” is a dirty word. They do it halfway, so it’s less effective.

I believe in propaganda because all art (the good stuff anyway) is propaganda. It’s how it’s used that matters; it cannot come from the lone dissenter—not the art necessarily, but the idea behind it. A lone voice speaks for the people. At its best: “I have a dream”—like the 92 bus on Glendale Boulevard, the LED screen reading, “I HAVE A DREAM” or a movie theater in Walker, Minnesota awash in pink. At its worst, it means tyranny.

III.

At a house party in Silverlake, I found myself talking to a guy who worked at SpaceX but “doesn’t hero-worship,” its founder and CEO. I mean, yeah, he’s gotten drinks with him, but that’s neither here nor there. He told me electric vehicles were the future, and Mr. Musk had some good ideas (gag me).

Ideologically, Elon Musk lives somewhere in the ecomodernist/edgelord/pro-whatever-the-fuck-is-best-for-him Venn diagram. Men like him believe a few lone dissenters will save us with byzantine, awe-inspiring solutions. Technology will save us, says the genius. Never mind wealth redistribution, corporate regulation, bike lanes, pedestrian-friendly roads, more housing, and better public transportation. You know, the stuff we figured out ages ago. The genius fights for “the shittiest ideas floating around, whose ‘proof’ could only be what they caused: over two thousand years of pogroms and witch burning and murdering and enslaving” (Morton).

The religion of technology, which I link here to Morton’s term scientism, believes in a future built by men whose actions have distorted our present, all for the sake of the “future.” Therefore, the future will save our future. What a circle-jerk load of bullshit. If your happiness and vision of the world rely on attitudes of obedience, you are the Devil (the demonic angel). You do not, have never known “better.”

The tyrant (like Blake’s Tiriel) doesn’t dream of freedom, only dominance. They deny religion, but they exercise its worst iterations all the time—full of “belief about belief” (Morton). Their religion is a still-warm gun directed at a crowd, demanding it to chill because the safety’s on.

Some rightly find religious institutions unforgivably abhorrent. The God people worship while committing every worldly atrocity becomes, through transference, atrocious: God becomes a symbol of evil. I know for a while, he was for me. But I agree with Morton when he writes, “Religion isn’t really about obeying patriarchy and racism and speciesism or even just doing as one is told: religion is about the mysterious and tremendous fact of being alive at all… its dreamy shuddering, a life-size rendering of the contingency and determinacy and vibration of a universe best described by quantum theory.”

Theory—if X is true, then we can suppose Y is… X is the leap of faith into Y. All science relies upon belief. Suppositions built upon other facts unknowingness. It is the only fact: we know nothing. It’s Blake’s “Holy,” Joyce’s “Yes,” and Maggie Nelson’s blue (Bluets): a vibrating electron of truth; unmeasurable and holy. Uncertainty is the pulse of science, and yet its principle is that “the physical world is determinate. There is blue energy and violet energy and ultraviolet energy and yellow energy. There is a rainbow of energy; there is no transparent energy” (Morton).

IV.

Blue, to me, best embodies this feeling. It is a feeling; I cannot call something so patently emotional an idea. Ideas have strings attached to them, pull at the thread to find the tension. But there’s no tension for me in blue, only a soft, mushy mess. It cocoons me and I am inside it. No light in blue, just engulfment. The simple dimensionlessness of a dot.

This only comforts me for so long: when you zoom in, the dot dissolves and it is us in the void. The void becomes everything, so we believe in God. We believe in signs and spiritual aberrations like fantastic forms of weather, which are around us more than ever. Tornados simultaneously suck up and collapse the world. We gamble and bargain with the earth for more time to ravage, but deep down we know something worse will come.

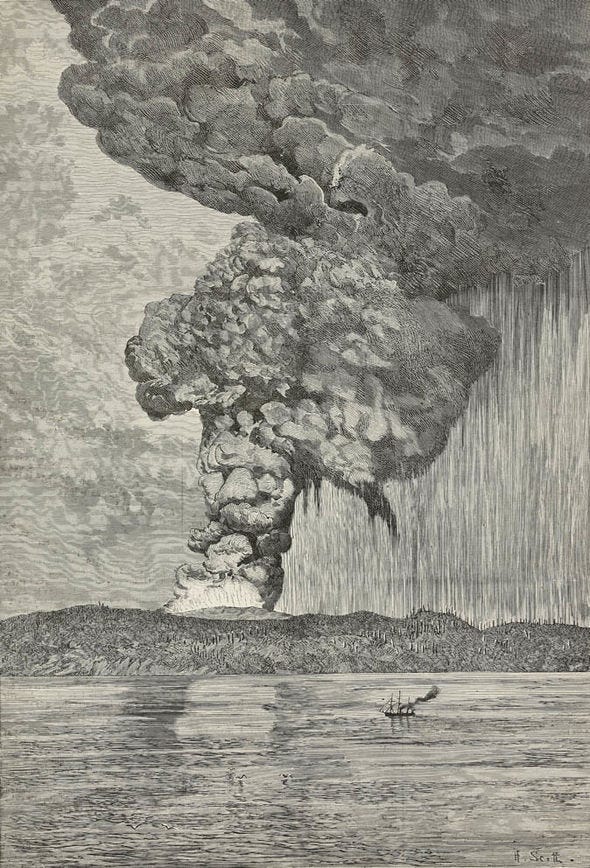

Sometimes I imagine Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein as a response to Percy Shelley’s atheism: we are both the scientist and the monster, she seems to say. The electric volt is God. The whole fact of our existence is surreal to the extreme. Evil exists and breathes, and maybe there’s never been anywhere safe in the world. After all, Mary Shelley wrote Frankenstein in the aftermath of a volcanic eruption called The Year Without a Summer. Hell has always existed, but “we must prefer real hell to an imaginary paradise” (Weil, Gravity and Grace).

V.

When I was a Christian I thought about God and fathers, but not much about life. I didn’t have many questions. I cried at the projection screen with Christian rock lyrics and called my mom, begging for forgiveness. When we were eleven, we all did. We were sinners, that much was clear. Twisting our souls from the inside, original sin lived within us. It wasn’t our fault, but we still had to pray it away. Wash the infection with saline solution. Only God can save you.

Admit you’re bad. Admit you’re the sinner, and all will be forgotten. The man looked me right in the eye—can’t you feel it haunting you, bleeding you out from the inside? Take the magic water and plunge yourself into it until you’re drowning in Him. Baptize yourself by admitting your fucked-up-ness. Become the demonic angel (Morton).

William Blake, again, flips it: baptize in your fucked-up-ness. Roll around in it, in everybody’s. Be glad to have a body that still lives. Be the angelic demon.

To Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love All pray in their distress; And to these virtues of delight Return their thankfulness.For Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love Is God, our father dear, And Mercy, Pity, Peace, and Love Is Man, his child and care.For Mercy has a human heart, Pity a human face, And Love, the human form divine, And Peace, the human dress.Then every man, of every clime, That prays in his distress, Prays to the human form divine, Love, Mercy, Pity, Peace.And all must love the human form, In heathen, Turk, or Jew; Where Mercy, Love, and Pity dwell There God is dwelling too.

“The Divine Image” by William Blake

VI.

Blake understood God, nature, the physical world, and, by extension, the physical form and how these phenomena blended into one. William Blake just fucking got it: the physical is divine. Think of the glorious blankness of a good fuck. The way heat encases a body in the desert. How both put us into full body awareness, a radical sublimation. What’s holier than that?

There seems nothing holier than the basest elements of desire; it reminds us that God is never enough. God is necessary, but he is not the only necessary thing. “If we want a love which will protect the soul from wounds, we must love something other than God” (Weil). And for those whose fucking (anyone not in the category of straight, white, men) has been stifled or outlawed, it can be an act of pleasurable protest. We say without saying we love something other than God, wiped clean by another body. Here you go—a plateful of humanity. Time and heaven are set aside, no longer “bound by unreal chains.”

In Wuthering Heights, Cathy says, “My love for Heathcliff resembles the eternal rocks beneath: a source of little visible delight, but necessary.” Necessary. For Cathy, loving Heathcliff is much like loving God. And when the necessity kills them both (his revenge and her obstinance), the hunger passes to their children. An inheritance of souls.

For the first time in years, I knelt on the linoleum and prayed and I was seven and fifteen again and God did not appear. I prayed for my idols and asked to keep them for a little longer (not yet). We all feel it: there’s a new flavor of urgency in the air and no God to obliterate the unrest. Like all the sickest cannibals, the void swallows the brain.

When I push God away, I stop seeing blue. I lose Blake.

VII.

Take Clarice Lispector’s The Passion According to G.H., whose narrator is sent spiraling when she kills a cockroach. The act shatters her very soul.

…rising to my surface like pus was my truest matter—and with fright and loathing I was feeling that “I-being” was coming from a source far prior to the human source and, with horror, much greater than the human.

Opening in me, with the slowness of stone doors, opening in me was the wide life of silence, the same that was in the fixed sun, the same that was in the immobilized roach. And that could be the same as in me!”

Lispector’s “I-being” is not “I” in the trick-mirror sense, but like Joyce’s “Yes,” and Blake’s “Holy.” “I” is not “I” but I-being; something bigger and holier. The cockroach is alive and so am I, therefore “I am the cockroach” (Lispector). Take Cathy, and my soaring, cracked heart when she says, “I am Heathcliff,” and what that says about how I love; my appreciation for the frail, fractured passion of conjoined souls. It is the kind of love I worship and fear, in turn.

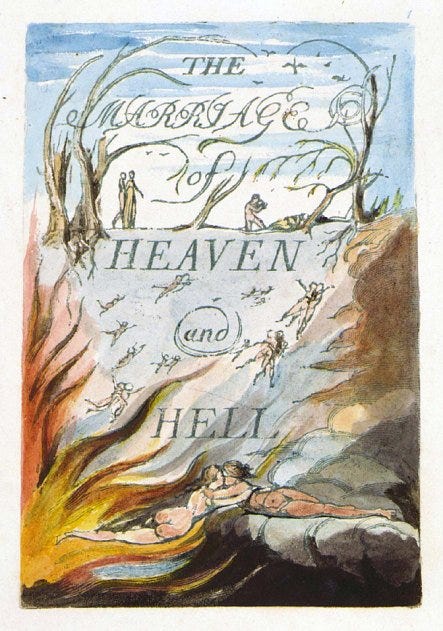

Love in the movies belongs to the future. In novels, it belongs to the past. As for the world, it lives in the air, glancing off clouds and ordinary objects. To touch is to love. It is to see and be seen. To know that one cannot know. It’s what people mean when they say love is a choice. Minute by minute, no love is the same; the very essence of distance. Between lovers and friends and trees, I cannot help but think that “every thing that lives is holy” (William Blake, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell).

God, to me, is the yes. My yes is blue.

I think of you in green, I remember he once told me

But when I go as I always must do

The color in his day will be clear and blue

“Morning Colors” by Linda Perhacs